BROKEN

PEACE

The city of Raqqa, in northeastern Syria, is under reconstruction. Guillem Trius.

Peace may be the end of war, but is rarely the end of suffering. Peace is not the moment when pain magically disappears. Peace is often incomplete, and is built step by step through small victories when the fighting is over.

Peace is often incomplete, and is built step by step through small victories when the fighting is over.

Peace is only made possible, through great effort, by anonymous people who stand together to rebuild what has been lost.

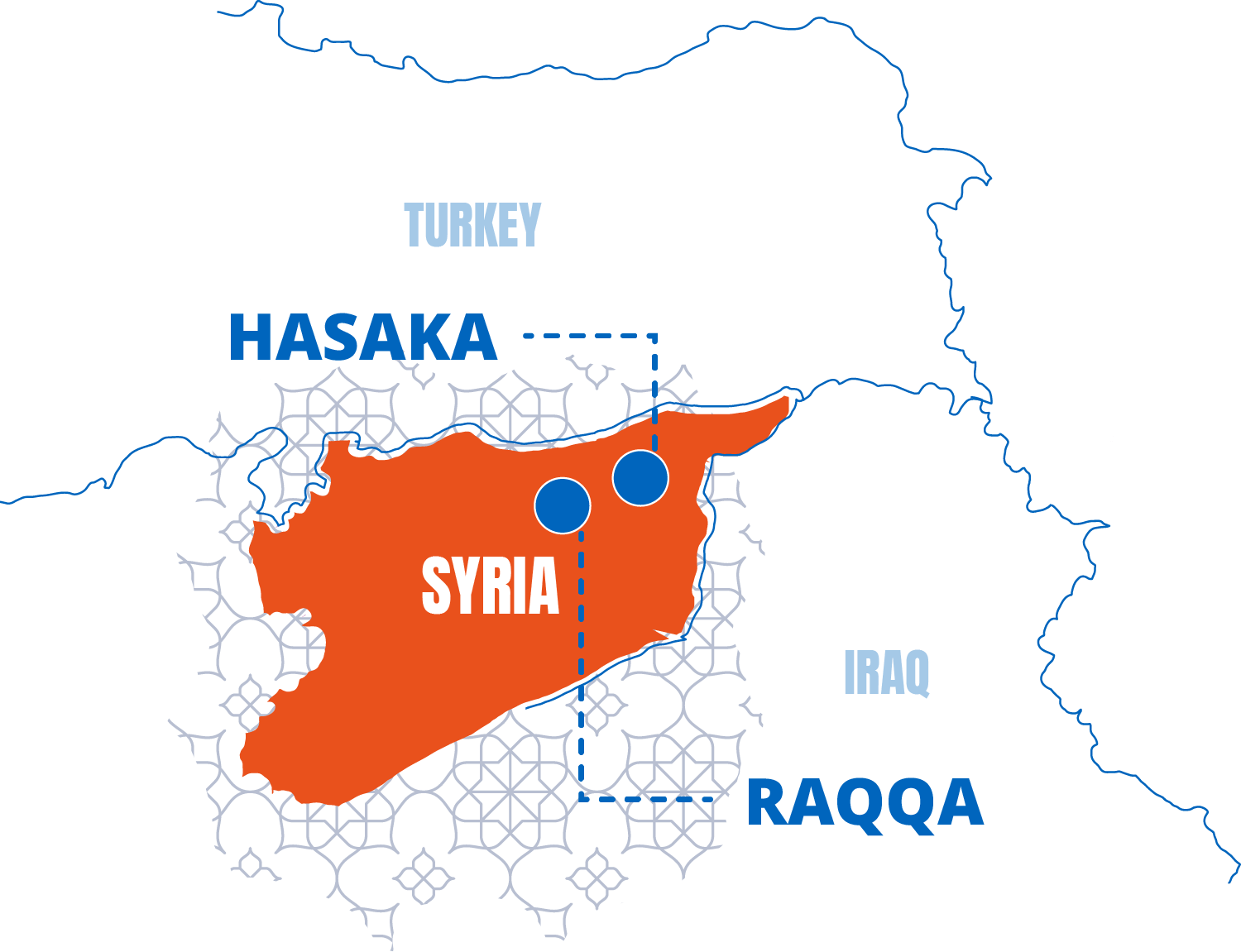

A good example of this is in north-eastern Syria (NES), where Médicos del Mundo has been working since 2017 with more than 20 health centers. Understanding what is happening in places like this is useful to understand what is happening all over the world.

The regime of Bashar al-Assad collapsed at the end of 2024. The world turned its eyes to Syria, especially to Damascus and the areas under the control of the regime. The focus of humanitarian action shifted there.

NES, which was not in the spotlight, has a different political reality and a different story. That is what we aim to show in this project — to explain why humanitarian needs are still urgent in this region that shares a border with Iraq and Türkiye.

“The needs are still there because the number of internally displaced people is still high. Basic services are not yet operational, and even the buildings still need to be rebuilt,” says Fatima Dreai, MdM’s field manager in Hasaka and Raqqa (NES).

Some of these areas experienced violent/brutal fighting years ago. Some were occupied by Islamic State (ISIS). New local authorities were established. Reconstruction began slowly, and thousands of displaced people arrived from other parts of the country. But with the change of regime in Damascus, uncertainty still hangs over this region, which has different social dynamics than the rest of the country.

Boys and girls playing on an abandoned bus in Hasaka. Guillem Trius.

In this environment, mental health plays a key role. It is one of the components of humanitarian action that is becoming more and more important. In the past, its significance was not fully understood, but in places like NES it is proving to be essential. People are fighting against the feeling of abandonment. And they are building a future. Like Nour and her radio show, Hassan and the shop he set up despite how much he suffered from the war, Samia and her fight to improve women’s lives, Amal and her concern for the mental health of her community.

Their stories show why it is important to keep working here. Their everyday victories are the basis of lasting change— a peace that must continue to be built, stone by stone.

Syria should not be forgotten

Outside the city of Hasaka in northeastern Syria. Guillem Trius.

War kills and injures many, but the collapse of local healthcare systems and services leaves thousands without care on a much wider scale.

A car enters a neighborhood on the outskirts of Hasaka, in north-eastern Syria (NES). A sandstorm has been clouding the landscape and now is dying down, but the air is still thick with dust. From inside the car, 38-year-old Amir Hadji and 35-year-old Dalal Hassan are trying to share/spread an important message to the community in this rural area.

Amir speaks for just a few minutes with a megaphone, and some neighbors step outside to listen to him more clearly. Next to a sheep, a man with a cane watches them with no expression on his face. Another man opens the gate of his garden and walks towards them. Three or four more people show up. Amir warns them about some of the most common diseases and tells them how to spot the signs of skin conditions, for example. He explains to them that primary health centers are available to them.

He is just reminding them that their needs should not be forgotten.

This kind of health promotion work is essential in areas like this, far from the main cities. War kills and injures many, but the collapse of local healthcare systems and services leaves thousands without care on a much wider scale.

Carrying medical leaflets, Amir and Dalal, members of the health promotion team, walk through the neighborhood. For now, the main concern is scabies. Amir and Dalal are welcomed by one of the community leaders, 40-year-old Mohamed Helwesh, who walks with the humanitarian workers towards his place. There, in the ground-floor living room, they sit down to talk. This dialogue is both work and solidarity. Mohamed will be responsible for sharing the leaflets with the 150 families living in the neighborhood.

Around the home of Mohamed, a community leader on the outskirts of Hasaka. Guillem Trius.

There is a broken window. Flies buzz around the living room.

“These leaflets are about scabies, leishmaniasis, children’s health…,” says Amir. “They are distributed throughout the neighborhood.”

“The problem is that during the war many diseases spread. Here we tell them how to prevent and treat them,” says his colleague Dalal. “Humanitarian organizations do their best to ensure these needs are met.”

“The main problem is unemployment,” says Mohamed, the community leader. “People don’t have jobs. They need help because they have no money. We need external support. MdM’s work is very good. They cover needs and help us prevent scabies and other diseases. There are people who don’t even know what scabies is, they don’t understand what’s causing their skin redness — until your staff came and explained that these people needed to go to the primary health center.”

“We drive around and contact community leaders,” says Amir. “Normally we are a man and a woman who work together so we can reach everyone. In remote districts, we communicate in Arabic and Kurdish with megaphones, informing about communicable diseases. We visit houses and neighborhoods to find out what diseases they have.”

“We have many leaflets and keep printing more. Before the war, there weren’t diseases like these, but poverty made them appear. The difficult situation led to more cases,” says Dalal.

Amir and Dalal leave the leaflets with Mohamed to distribute among the neighbors. Then they leave. Until the next day

Médicos de Mundo community centre in the vicinity of Hasaka. Guillem Trius.

When the Lights Go Out

Women defend their rights. I work so my children can eat. I am proud of that.

This has always been a hard-to-reach area. It went through difficult times. People are now trying to overcome the situation. But it is getting no media attention—neither globally nor within Syria.

“The focus of many organizations is on Damascus and the areas controlled by the previous Syrian government, which were inaccessible before,” says Fatima Dreai, MdM field manager in Hasaka and Raqqa (NES).

This is not the only factor at play. Humanitarian aid funding cuts by the U.S. government have affected the entire system, and this region is no longer seen as a priority. There is a post-war feeling in the air. There is much to rebuild. With some help, things can move quickly. But without that help, everything will be harder.

During the civil war, independent structures developed in NES, which covers roughly one-third of the country. This is now known as the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES), controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). They are Kurdish-Syrian militias that played a significant role during the conflict. They were instrumental in the fight against ISIS, which managed to take towns like Raqqa and Kobane, near the Turkish border.

Now that NES is gradually integrating into the new Syrian state following agreement with the government, only time will tell what the future looks like for the population.

It is a complex and uncertain political, social and humanitarian environment the people in NES are made to witness and experience. In a region with towns like Raqqa still halfway through reconstruction, medical assistance proves essential. Médicos del Mundo operates in the area, supporting 22 centers.

“We need more help from outside, more support, especially for heart conditions and diabetes,” says Jumana Ahmed Abid, who works on a health committee of the Kurdish-Syrian authorities in the region. “We need more resources for treatments. Medicines are lacking; we need more help from organizations.”

Wearing her white scarf and green dress, 56-year-old Jumana Ahmed Abid speaks from one of the primary health centers in Hasaka province.

Jumana Ahmed Abid works on a health committee of the Syrian Kurdish authorities in northeastern Syria. Guillem Trius.

“We have provided information to women about breastfeeding, drugs and gender-based violence,” she says.

She emphasizes the essential role women play —not just as patients or beneficiaries, but as active members of civil society striving to build peace.

“Women defend their rights. I work so my children can eat. I am proud of that.”

Jumana Ahmed Abid regrets that some organizations have stopped operating or reduced their activities in the region.

“The war has caused many diseases in the country,” she says. “I hope aid reaches all of Syria, but also here, especially for displaced people.”

NES should not be forgotten. Jumana and thousands of people fight to ensure this does not happen.

Displacement and Mental Health

Camp for displaced people in northeastern Syria. Guillem Trius.

I’m very angry. I want to go back home. I want to go back to Afrin. I want a solution.

This is a school transformed into a shelter in Hasaka (NES). Three stories high. Sad, shattered, almost in ruins. Thirty-four families live here. Thirty-four families, thirty-four routes, thirty-four dreams. For these people, the war is not over. Worse yet —they had to flee when the war everyone talked about seemed to have ended.

They are from Afrin, a Kurdish town in northern Syria, outside this autonomously administered region. The fighting forced them years ago to seek refuge in the nearby town of Shahba. But after the fall of the Syrian regime, after the theoretical end of the civil war, they had to flee again. There were clashes between the SDF and armed groups supported by Türkiye. A last episode of the war unheard by much of the world, which kept its eyes on Damascus.

Thousands of people fled. Like the thirty-four families sheltered in this school supported by MdM.

“I went to the doctor, but there’s no solution,” says 80-year-old Maryam Ali, sitting in her wheelchair in a hallway of the school.

Since she had a stroke, she can barely move her legs. Children, family, and fellow residents surround her. They help lift her right ankle to place her leg on the chair.

Maryam has taken refuge in a school in Hasaka. He fled fighting in northern Syria. Guillem Trius.

“We were forced to move here. We arrived a few months ago from Shahba,” says Maryam, with a violet and white scarf.

“There’s no attention to what’s happening here. They don’t care about us,” she says, but her speech is interrupted as she starts coughing, choking. She wants to keep talking, but cannot. Someone offers her some water.

“I’m very angry. I want to go back home. I want to go back to Afrin. I want a solution.”

This sentiment is shared every sheltered resident in the school.

“All my clothes stayed in Shahba. I hope the situation improves. I still have hope that it will. We’re still suffering. We will go back to our country.”

Maryam is not alone. Her family has 16 members —in this school, her children and granddaughters live in the classrooms where displaced people have been temporarily settled.

But some of her family members are not here.

“Two or three of my relatives have gone back to Aleppo province and say the situation is not good. One of my sons lives in Europe. He wanted to bring me to Europe, but he couldn’t,” she says.

In the schoolyard, the worn-down basketball backboards look lonely. Boys and girls run back and forth. One of the boys complains that they do not even have a ball to play with.

The Escape

Médicos del Mundo supported health centre in north-east Syria.

Mental health has been ignored in conflicts. But the burden that people fleeing carry with them is not only physical, but also emotional.

The fall of the Syrian regime sparked a public debate about what would happen to the millions of refugees who fled the country during the civil war. Uncertainty remains in the Syrian political landscape, and since then over 400,000 people have returned to Syria, according to the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

But what about those displaced within the country? Internal movements respond to complex national and regional dynamics. In NES, wounds from the past and present compound. Until December 2014, there were more than 300,000 displaced people in the region, caused by fighting in different parts of the country and especially by the expansion and subsequent expulsion of ISIS. But recent violence in the Aleppo province, from which Maryam and her family fled, caused the displacement of over 26,000 people to temporary centers like the school in Hasaka. There is more willingness to return immediately among this latter group than among the first. In any case, they all need help.

And they are working together in order to move forward.

Children in a school used as housing for refugees. Guillem Trius.

Emotional Intelligence During the War

We have all been affected by the war. I was forced to move twice. In 2016, a relative died. It took a heavy toll on me. My husband then said we would all lose someone in the war. Life goes on. Life went on.

This psychological stability is hard to achieve in daily life. But it is even harder to achieve after more than a decade of war.

38-year-old Samia improved her mental health after sessions with a Syrian psychologist at the center. She tries to implement the things she learns in the sessions in her daily life. Sitting in the consultation room, with a long braid and a purple shirt buttoned up, arms crossed, she gestures with her fingers suggesting her head is spinning, she is always thinking.

“We have all been affected by the war. I was forced to move twice. In 2016, a relative died. It took a heavy toll on me. My husband then said we would all lose someone in the war. Life goes on. Life went on. I found a job, and that gave me stability. Without a job, there is no stability.”

Samia goes for psychological consultations at a health centre on the outskirts of Hasaka supported by Doctors of the World. Guillem Trius.

When she feels anxious, Samia takes a deep breath.

At the primary health center she attends in Hasaka province, there are handprints painted on a wall, a TV playing health messages, a mental health consultation room, a paediatric surgeon, a delivery room, and a poster celebrating International Women’s Day, March 8, with the pink ribbon for breast cancer awareness and tips on prevention.

Samia radiates warmth and light —just like another beneficiary, 43-year-old Afra Def el Barhom, who is wearing a white headscarf and a handbag. She shows constant trust in her psychologist, Amal Issa Sheikho, who sits beside her in the consultation room.

“I’ve been living here for two years, in a rented house. When I come to see the psychologist, I feel better. It changes my mood.”

Afra found the health center on her own. She says that normally the cost of medical services would be too high, but here they are free, which is why she is able to access them.

Sitting next to her, Amal, the psychologist, adds: “When Afra came, I could see she was under a lot of pressure. She was already taking care of her siblings —and also took on the responsibility of looking after their children. But she has a disability [a congenital malformation in her arm], and I told her maybe she shouldn’t have to do all that. She arrived here in 2019 after an attack by armed groups.”

Afra is from Ras al-Ain. Thousands of people were forcibly displaced from there.

“We’re all displaced in my family. I also care for my parents. They’re sick, and they come to this health center too,” says Afra. “When I first arrived, I felt so sad, but then life improved, and I started to believe the future would be better. The psychological support helped me through everything.”

Refugee family in the vicinity of Raqqa. Guillem Trius.

Mental Recovery

People don’t know what their future will look like. They don’t know if they’ll have to face displacement again.

Afra and other patients have a strong trusted relationship with the psychologist, Amal Issa Sheikho. She is good at her job. At 32 years old, she understands the cultural, social, and emotional realities of her community —and knows how to use the tools available to improve the lives of those around her, many of whom have been forced to flee their homes due to violence.

“In the beginning, people didn’t trust this [mental health] service because mental health is often minimized,” says Sheikho, sitting in her consultation room after Afra, the patient who admires her so much, has left. “But gradually the results started to show, and now people come even without us having to tell them.”

“We see all kinds of patients,” she says. “Internally displaced people who have lost their homes, people suffering from depression or anxiety, some in uninhabitable conditions… There are also young people from here who feel uncertain about their futures and are under pressure. And of course, there are people affected by poverty. We try to help them all.”

The words of Afra and other patients are not exaggerated —Sheikho works to heal psychological wounds, but does not patronise or victimise.

“We offer individual sessions, group therapy, referrals, resources… We give them hope, positive ideas, we strengthen the facets that empower them. Every person is born with inner strengths —we just try to activate them,” she says.

Sheikho does not onlt focus on the war’s immediate mental toll. Instead, she emphasizes how the broader context of political and economic uncertainty weighs on people. Stress is a recurring theme in her sessions.

“People don’t know what their future will look like. They don’t know if they’ll have to face displacement again. Some haven’t received their salaries since the regime collapsed,” she says.

All of this is echoed in the stories shared by other patients, like 29-year-old Zein al Abideen, a fourth-year architecture student. His words embody the fractured sense of future Sheikho often refers to, especially amongst young people.

“I felt weak. I was dealing with depression, but I didn’t even realize it. That’s why I couldn’t finish my degree earlier,” Zein says. “With Amal, we slowly dug into my situation. At first, I didn’t believe she could help me —but she did. I was lost. She taught me breathing techniques. She even recommended books.”

The book she recommended to him was The Fantastic Victories of Modern Psychology, by Pierre Daco.

“Amal knows me well,” Zein says.

A Radio Show Can Heal Minds

We must not judge anyone’s feelings. That’s very important. We shouldn’t get obsessed over small details.

A radio studio in Raqqa, north-eastern Syria. A journalist and a psychologist. A faint blue light.

“What are the behaviors that help promote mental health?” a journalist asks.

“Open communication,” replies Nour Darwish, a psychologist who collaborates with MdM. “You have to rest, and the family must understand this behavior. You should not be judged, because that has a great impact on emotions.”

The logo of the radio station, Al Rashid FM, at the back wall of the studio, is lit by spotlights. The lights change color. From red to blue, from blue to violet, from violet to green.

“Families are going through many crises…,” says the journalist. “How can we reduce their impact on people’s mental health?”

“There must be peace within the family. It must be united to reduce anxiety levels,” replies Darwish with confidence. “We must not judge anyone’s feelings. That’s very important. We shouldn’t get obsessed over small details.”

“But if family relationships aren’t good,” the journalist says, reading from the script, “what consequences does that have on its members?”

Darwish answers without looking at the papers lying on the studio desk, where her handbag also lays down. Both are recording a radio show that will air a few days later and will be shared on social media.

This week’s topic is family. At 29 years old, Darwish frequently participates in this Al Rashid FM show, which delivers messages to the community about health and specifically mental health. One of the shows is called My Health, and another one is called The Eve, where topics related to women’s rights are often discussed.

After the recording, in the same studio, Darwish explains her motivation for participating in the radio show, and how she balances this collaboration with her work as a psychologist.

“We talk about women, gender-based violence, discrimination. The audience already recognizes my voice. They know it’s me,” she says.

Together with the journalist, she agrees on the weekly topic and writes a script with at least 15 open-ended questions. The long-term consequences of the war are always present.

“The war has caused a lot of pain, a lot of fear,” says Darwish. “People still see mental health as a stigma. They don’t want to talk about their fears. The same thing happens with gender-based violence.”

The scope is expanding. About a dozen psychologists participate in shows on this Raqqa-based station, covering topics such as vaccines, breastfeeding, or leishmaniasis. They choose what to discuss based on current events, community needs, or what is observed in local primary health centers.

“We talk about issues that affect the community,” says Darwish. “But as a psychologist, many of my patients are women. So I usually choose topics that are relevant to women —or that women suffer from. We try to support them.”

A Radio Show against Loneliness

But who listens to these radio shows? Who receives these messages?

People like Hala Hamo, a 27-year-old Economics graduate. Hala discovered Nour’s show and got immediately hooked to it.

“I used to suffer from anxiety, and I didn’t know how to manage it. I started listening to Nour, and she taught me really important things. All the topics she covers are relevant —stress, anxiety, women’s issues…,” she says.

Hala appreciates that the show doesn’t just focus on theory but also includes real-life cases. Nour tries to communicate clear messages to her audience —and she succeeds. She connects with people.

“The topics Nour discusses are so important for my friends and me. They reflect our real problems as a community.”

And she can do this, among other reasons, because she listens to the audience. Hala and her friends have reached out to Nour to suggest topics, to share their concerns, so Nour can address those issues on air.

“It’s like psychological therapy,” says Hala.

This could be the story of any radio station in any remote part of the world. But there is an important detail —this country has suffered from more than thirteen years of civil war.

“I was still carrying a lot of grief over the deaths of my father and brother. The radio show helped me a lot,” says Hala.

They were killed in an attack by the former Syrian regime in 2013. She never really overcame it —how could she? The war continued. But she found a small source of comfort through the radio waves.

“I found this show, and it made me feel better,” says Hala.

After the War

Uncertainty hangs over the minds of the civilian population in northeast Syria. Guillem Trius.

Hassan is an indirect victim of the Syrian war. He had diabetes, but his city was occupied by ISIS and he didn’t receive adequate treatment.

A road on the outskirts of Raqqa, the former capital of ISIS in Syria. On the sidewalk, there is a stand —a street shop for children and teenagers, with balloons, chips, juices, sweets, chocolates. Some groups of schoolchildren passing by look at its owner, Hassan Naif al Hilo, who waits for customers while he is having tea and eating some bread and yogurt. Behind the stand there is a shop, a closed room.

Entering there means entering a different world —antiques, broken clocks, irons, switches, big calculators, light bulbs, small stoves, knives, phone cases, nail clippers… It is a second-hand business through which 83-year-old Hassan made a dream come true.

A candy store and a second-hand business to start a new life. It is not a cliché.

“It’s a simple idea… It was my idea,” says Hassan, touching his head as if to say, “I thought of this myself.”

Hassan is one of those war victims whose stories we do not usually hear. He was not injured by a bomb, nor did he lose family members in the war. He is an indirect victim of the war. Bombs do not only have a direct impact on civilians; they often leave them with little to no medical care. A war is not only about the wounded soldiers, but also about people suffering chronic illnesses who urgently need help.

Hassan sufrió la falta de atención médica durante el conflicto. Ahora lucha por salir adelante. Guillem Trius.

When there is war, small problems become big problems.

That is what happened to Hassan. His town, in Raqqa province, was taken by ISIS. Health services stopped working for the civilian population. And then he had a strange feeling.

“I had problems, I felt bad, my legs were getting gangrenous,” says Hassan. “ISIS occupied my town, the situation was very complicated, there were no hospitals. If I had received treatment, the situation would have been different. All this is due to late treatment. This is the result.”

Hassan is referring to his leg prosthesis. It is not obvious unless he refers to it —he limps a little when walking, but moves with agility. He is 83 years old but he looks younger.

In 2015, Hassan was able to leave Raqqa to go to Beirut, the capital of Lebanon. He paid for the trip himself, but once there, he asked for help. He was diagnosed with diabetes.

“They told me they had to amputate a leg because it was gangrenous. They gave me a prosthetic leg,” says Hassan, who received support from humanitarian organizations during this process.

He went back home. He faced his new reality. Hassan has a large family: seven sons and four daughters, and many grandchildren. In Raqqa province, after a few years, he started attending a center supported by MdM. The mental health consultations helped him look to the future. Psychosocial support encouraged him to carry out a small idea: a candy shop and a second-hand goods store where he would buy items to resell them.

“The outside store is for the children, and the inside store is for special customers,” says Hassan. “I have customers who say they are missing a special piece, or need to repair gas pipes… I have experience with this second-hand stuff.”

Hassan walks through his store in black sweatpants. He walks among aluminium trays, tape recorders, scissors, locks, dish racks, even old jackets. He is in no hurry. The routine, the opening and closing hours of his shops, gives him peace of mind, a roadmap. He no longer looks back.

“I don’t regret anything,” says Hassan. “You have to move forward.”

A New Life for Fatima

Fátima fled the conflict. She now works at a healthcare center supported by Médicos del Mundo and is rebuilding her life. Guillem Trius

45-year-old Fatima Mustafa al Marray feels the same.

This primary health center on the outskirts of Raqqa is tidy. But above all, there is a sense of cleanliness. It all has a calming effect on the general mood. The smell of disinfectant permeates every room without being overwhelming. The center has a mental health consultation room, an emergency ward, white walls, a poster about water purification tablets, and in the middle of the hallway, a waiting area.

This is where Fatima works. She is from Tel Abyad, near the Turkish border. She arrived here, to this town outside Raqqa, in 2018. You can feel the fire of survival and the caution of humility in her eyes.

“There was fighting between ISIS and the regime. ISIS kidnapped my husband. To this day, I don’t know where he is. I have two sons, they are 6 and 8 years old,” says Fatima in one of the hospital rooms.

She fled Tel Abyad with her children. Her main fear was obvious at the time —war. But then her priorities shifted. Alone with two young boys, she needed to find a job.

“We found safety here. But at first, I had nothing. My sons weren’t in school, and people gave me charity. Sometimes we went without food,” says Fatima.

The health center was about to open, and Fatima offered to volunteer. Eventually, she was hired to work in the cleaning service.

“Now I have a salary, my sons go to school, and I can make sure their needs are met. I’m happy with them and with my job,” she says.

The previous years, without her husband and with no family support, were hard. But in April 2024, when she started working at the center, everything changed.

“There are three of us cleaners at the center. I work 24-hour shifts and then rest for 48 hours. The school is nearby —I walk the kids there. I’m proud. I did everything I could to get this job.”

Fatima knows, feels, accepts, that her husband is gone forever.

“I have no hope of seeing him again,” she says, as she starts to weep. “I have no idea if he’s even alive.”

But now Fatima is focused on the present. She survived the war, she survived economic hardship, and now she only wants to look ahead.

“Thank God I found safety for my children. There were times when they had no bread, no clothes. Seeing my sons go to bed hungry made me stronger. Poverty gave me strength.”

Médicos del Mundo España

Conde de Vilches, 15

28028, Madrid

De lunes a viernes de 8h a 20h.

Teléfono 91 543 60 33

Email: informacion@medicosdelmundo.org